From this weekend's edition of "The Lewis County Catholic Times"

We

have spoken on a couple of occasions about the four axes of the liturgical year—both historically and in our modern

times—on which the entire Mystery of the Life of Christ reveals itself through

our common worship. These days are

Christmas, Epiphany, the Paschal Triduum, and Pentecost. Each in their own way manifests to the world a

fundamental aspect of who Jesus is, of what his mission of Salvation has

achieved, and how we are called to respond to it.

Of

course we know all about Christmas. Not

only is the event poignant and heart-warming, but it also has lent itself to

cultural appropriation. It has joined so

seamlessly with our own consumerist mentality, wherein the likes of Charles

Dickens, Bing Crosby, Frank Capra, et al., have helped to form the Courier

& Ives-esque image of a day that hinges on the retail-industrial

complex. We not only enjoy it—we base

our national economic well-being on it.

Easter

holds its own and gets a fair amount of attention. But even though it has traditionally been THE

holy day for the Church throughout history, in our culture it always plays

second fiddle to Christmas. The songs

just aren’t as catchy as Christmas carols, Easter baskets cannot hold a candle

to presents under a tree, and the Easter Bunny is no match for Santa

Claus!

Epiphany

has almost become a throw-away day, being transferred here and there on the

calendar in order to accommodate the increasingly busy schedules of western

Catholics. As the 12th day of

Christmas, it is the day on which the Christ Child is manifested to the whole

world as King and Savior through the eyes of the Magi. But it rarely gets the recognition it

deserves.

Historically,

as has been featured in this publication before, Epiphany and Pentecost were

the two hinges of the “ordinary time” of the calendar. But those days were far from ordinary, as

they were firmly rooted in the theme of the particular days. So if Epiphany focused on the saving action

of Christ in his earthly ministry, then Pentecost is given to us for the

purpose of taking that message out to the world.

Pentecost

(which means “fifty”) was celebrated by the Hebrew people to mark 50 days after

Passover. One of the three pilgrimage

feasts of Israel (cf. Leviticus 23, Deuteronomy 16), it was not originally

associated with an historical event, a la Hanukkah or Passover. In Leviticus it is called “The Feast of

Weeks,” a one-day festival that marked the beginning of harvest season. Both Leviticus and Deuteronomy stress that,

during the harvest, special consideration was to be given to provide for the

poor and the aliens in the land (Lev. 23:22, Deut. 16:11-12). Based on dates that we can glean from Exodus

19:1 (when the Hebrews arrived at Mt. Sinai) the feast of Pentecost was expanded

to include a commemoration of God giving the Law to His people. The Book of Ruth, with its themes of harvest,

was often read at this time in Jewish tradition. For Catholics, our own liturgical tradition

yielded Rogation Days (which exist in law but rarely in practice), which were

days of intense prayer directed by a Diocesan Bishop principally for the

intention of a good crop yield. For

reference, the Rogation Days which were built into the liturgical calendar up

until 1969 would have been observed just a couple of weeks ago.

Often

when we think of Pentecost we link it to thoughts of the Birthday of the

Church. On the day of Pentecost,

according to the second chapter of the Acts of the Apostles, God poured out the

Holy Spirit on Our Lady and the Apostles, endowing them with the Gifts of the

Spirit that they would need to fulfill his Great Commission to go out and make

disciples of all nations.

This

day, then, should be an occasion for us as the Church of Christ to

celebrate. And yet what is generally

regarded as the day dedicated to “the forgotten Person of the Trinity” often

becomes just another Sunday. When we

contrast the pomp and circumstance of Christmas and Easter with the relative

silence of Pentecost, it is more than just a little perplexing. Perhaps a cynic might view the situation

according to a consumerist model: “If we can’t use it to buy/sell stuff, then

it has no value.”

Perhaps

we have forgotten the words of Jesus: “…it is to your advantage that I go away,

for if I do not go away the Advocate will not come to you; but if I go, I will

send him to you” (John 16:7). Jesus

Himself tells us that the coming of the Holy Spirit is going to be the best

thing that ever happens to us. The

outpouring of the Spirit is the capstone to everything that Jesus began in His

earthly ministry. He, who became

incarnate, was revealed to the nations, was crucified, buried, raised, and

ascended, is now enthroned in Heaven, and from that throne He sends His Spirit

to enshrine in our hearts the New Covenant which He established in His Church.

“The days are surely coming, says the Lord, when I will make a new covenant with the House of Israel and the House of Judah. It will not be like the covenant that I made with their ancestors when I took them by the hand to bring them out of the land of Egypt, a covenant that they broke, though I was their husband, says the Lrod. But this is the covenant that I will make with the House of Israel after those days, says the Lord: I will put my law within them, and I will write it on their hearts; and I will be their God, and they shall be my people. No longer shall they teach one another, or say to each other, “Know the Lord,” for they shall all know me, from the least to the greatest, says the Lord; for I will forgive their iniquity and remember their sin no more” (Jeremiah 31: 31-34).

“I will sprinkle clean water upon you, and you shall be clean from all your uncleanness, and from all your idols I will cleanse you. A new heart I will give you, and a new spirit I will put within you; and I will remove from your body the heart of stone and give you a heart of flesh. I will put my spirit within you, and make you follow my statutes and be careful to observe my ordinances…” (Ezekiel 36:25-27).

And

so the day that was originally identified with the giving of the Old Covenant

Law now marks the New Covenant in action!

The giving of the Law, fulfilled in Christ Jesus, now progresses to the

next great age of humanity in which God no longer gives us His Law in stone but

writes it in the flesh of our hearts.

The announcement of the harvest now becomes beginning of gathering of

the nations into the umbrella of the Church.

The command to remember the poor and dispossessed is fulfilled in the

Body of Christ which becomes increasingly diverse and manifests itself in

unselfish, self-sacrificial love for others.

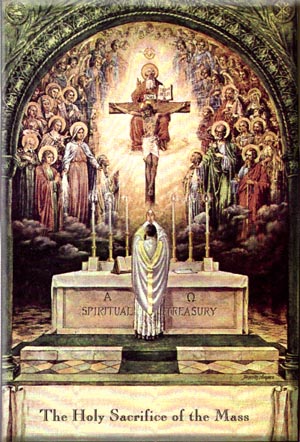

The Risen and Victorious Lord, now seated at the right hand of the

Father, pours out His Spirit on God’s people!

It

is our day of victory, our day of joy, our day in which—once again—God fulfills

His promise to His People. May we all

receive the Holy Spirit into our hearts with the joy and enthusiasm of the

Apostles, that we, too, might go out to the world and make disciples of all

nations!